The theme of victims’ rights was a common, distinct thread across all three days of the World Congress Against the Death Penalty in Geneva. It cropped up in different guises and from different angles in both open plenaries, in the workshops and roundtables, and came into its own during the incredibly moving ‘Words of Victims, Voices of Experience’ theatre evening.

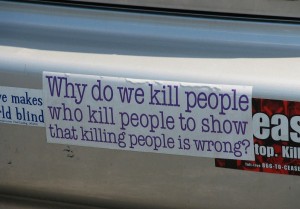

Renny Cushing of Murder Victims’ Families for Human Rights told us that many speak of the death penalty as a way for those left behind to achieve healing, justice and closure, when in fact many of the bereaved reject the notion of ‘closure’ completely. Coming to terms with loss is one thing, retribution is quite another. Having sought opinions widely on this matter, Renny has been given many reasons which emphasise that the death penalty is the wrong solution for the victims.

‘Having someone murdered by the State does not give me what I need,’ people say. ‘It would be better if the resources spent on maintaining the instruments of capital punishment were to be spent on other things: assistance for victims’ families and close friends, better crime prevention, resourcing for police, DNA testing to help solve unclosed cases.’ Now THAT is justice – diverting dollars away from needless vengeance and into resolution, and perhaps even more importantly, into reparation. Many people do not consider the burden cast on the families of those murdered. Renny himself recalls how, after his father was shot dead at point blank range, in his own home, his elderly mother, who had witnessed her husband’s killing, received an invoice in the post for the cost of the ambulance to take her husband’s body away to the morgue.

‘I can’t believe I have to pay for my husband’s murder,’ she said at the time. In short, there is little or no understanding of victims’ pecuniary needs after murder. There is the cost of the funeral to bear, the loss of income both from the victim and from the grieving family, and no form of compensation. To rub salt into the wound, it often seems like the State does not blink at the expense involved in an execution; yet gives no thought to the needs of those who have been harmed emotionally, pyschologically and financially by the wrongdoing. Renny, for one, believes the USA has this all wrong, when the (often very extensive) emphasis is on the death of the perpetrator, rather than the dignity of the victim and his or her family.

James Abbott, the New Jersey Chief of Police, agrees with him. ‘There is no way to fix the Death Penalty and make it right,’ he affirms. His sympathies in murder cases have always been squarely with the families of victims. The stress of the protracted appeals system does not in any way bring closure; it just gives almost celebrity-level attention to the perpetrator. ‘Just stop and think how many high-profile murderers you can name. Now name their victims,’ he says, and we nod in agreement.

And then there is the cry for compassion: ‘My loved one(s) has/have already died. Why add to the death toll and create a world of suffering for someone else’s family?’

These are powerful messages coming from the mouths of people who have suffered the worst anguish imaginable. Fortunately, they have had an impact in New Jersey, where the death penalty was abolished in 2007. Chief James Abbott was part of the commission set up to report on whether the state should abolish. At the outset, he was personally pro-death penalty. He admits, he still has views which would favor it for certain crimes; but now he knows that capital punishment is not a workable form of criminal justice. Often, he is asked ‘But what if it were a police offer who was killed?’ His answer is still that execution is not the answer. He would not want any officer’s family to suffer the way he knows others have, forced to be reminded through a protracted and flawed appeals process of their tragedy, while simultaneously being ignored in the aspects where it matters. Instead, a system which guarantees that the guilty party is behind bars for life, and which provides support for the family of the victim, is a far better solution. LWoP (Life without Parole), he adds, is fairer on a socio-cultural basis, prevents the risk of wrongful execution and assists families to recover.

John Van de Kamp, former DA of Los Angeles and Attorney General of California, has always been an opponent of the death penalty, but spent many uncomfortable years in prosecution, condemning many to death. Today, he is free to state his mind. He knows that in California, popular support for the death penalty is high, but his experience shows that this is largely down to society’s fear of recidivism.

‘People don’t believe that Life without Parole truly means life. And yet there are no examples of LWoP prisoners being released, other than as a result of exoneration.’

Polls show a huge drop in favor of executions when people are offered the alternative option of ‘guaranteed real life’ (LWoP). This is even higher when LWoP + work-based restitution is an available choice (i.e. make convicts work to earn their keep and deliver compensation to victims’ families).

But what about other countries, where vengeance is de rigueur? We heard in Geneva from Toshi Kazama, a Japanese photographer, and survivor of a murder attempt in which he was left for dead and was unconscious for three days. Toshi had already been responsible for photographing victims’ families, inmates, execution chambers in the USA and has met many families who have shown compassion to perpetrators. This, says Toshi, helped him to get through his own experience. However, if he were at home in Japan, reconciliation through compassion would be nigh-on impossible.

‘There, as with many Asian communities, it is a collective society,’ explains Toshi. ‘You have to fit the accepted framework. You must HATE the perpetrator.’

In Japan, it is most unusual to support the perpetrator and ask for clemency, and it leads to the victim becoming an outcast; indeed a victim twice over. Those who do not seek vengeance against wrongdoers are treated as outcasts, and become subject to bullying and intimidation. Often families are forced to separate so as not to have one person’s desire for clemency reflected in punitive social actions being meted out against those closest to them. Voicing free opinion and compassion is simply taboo, having a contrarian view in capital punishment goes against culture. Although many victims will say in private that they do not want the death penalty brought in their case, they continue to argue it in principle. It is a similar story in Taiwan and in China, where the same issues arise from the collective nature of society. So it is virtually impossible for individuals to find peace through open forgiveness, as this would almost certainly lead to their own victimisation.

Toshi believes education is very important in this respect. He take victims’ families groups, including Murder Victims’ Families for Human Rights (MVFHR) to Japan and Taiwan. In 2010 a further tour is planned, during which Toshi hopes to tell many people ‘It’s OK – the victim’s family can react how they want to react to handle their pain. They don’t have to adhere to the framework and norms.’

Elsewhere more sympathetic measures are being taken to help victims on the road to healing. Mariana Pena of the International Federation of Human Rights (FIDH) spoke to us of victims’ rights at the international level. In France, victims have a legal right to act in partnership with law enforcement and criminal justice elements to bring about justice for their case and seek reparation. Reparation can include both restoration – coming to terms with what has happened, often via reconciliation with the criminal; and satisfaction, meaning the honouring of the victim. Opportunities are increasingly given for the victim to participate in justice, and this is important because it impacts the victim on many levels: emotional; psychological and financial. In too many countries, the victim is ignored. Acknowledgement of suffering can help with the psychological healing process although it can be very traumatic for the victim… and requires psycho-social assistance from the state or NGOs.

Retribution: the need for vengeance is primal, a gut reaction to being hurt or seeing a loved one harmed. Many, many victims know this is not the solution to their grief. However in some countries and regions, vengefulness is seen as the norm; here, it can be difficult for a non-conformist to ever come to terms with loss. FIDH hopes that advocacy for legal reforms at international level will lead some countries to replace the death penalty with more reparation and support for victims.

Rehabilitation and Redemption: both James Abbott and John Van de Kamp spoke of the need for opportunities for offenders to seek redemption through work and rehabilitation. One such way would be for reformed LWoP prisoners to undertake to assist in education programmes for young people.

Reparation, satisfaction, restitution and compensation, remedy and redress: these are all things that the justice system could help to achieve for the victim’s family.

Restoration and reconciliation: we heard in the previous post how Bill Pelke of Journey of Hope has found peace through forgiveness. Restorative justice clearly has a role to play here and it will be intersting to see whether the success which some countries have seen in this area, particularly with young and first-time offenders, might ever have an effect on the scale of murder and life imprisonent. It would be nice to have a chance to find out, but we’re going to have to ditch the death penalty first!